There is a growing consensus among hemp advocates that the 0.3% limit for THC content is arbitrary and is holding back the industry. And the man widely credited with arriving at this limit himself agrees.

There is a growing consensus among hemp advocates that the 0.3% limit for THC content is arbitrary and is holding back the industry. And the man widely credited with arriving at this limit himself agrees.

The Contested Border

"It seems like it is pretty much pulled out of air. We ought to be looking to science to determine an appropriate threshold, determine the level at which cannabis is psychoactive and make that the standard."

This typical view is offered by attorney Patrick Goggin of Hoban Law Group, the international firm specializing in cannabis. Goggin is one of the industry's legal heavy-hitters, and has particular experience in the question of the contested border between hemp and marijuana.

He was co-counsel in HIA v DEA, in which the Hemp Industries Association argued that no-THC parts of the cannabis plant, including stalk and sterilized seed, are exempt from the Controlled Substances Act. In a 2004 ruling, the US 9th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, shooting down proposed DEA rules specifically controlling these products. The 9th Circuit said in its opinion that rescheduling of cannabis should be broached.

Goggin was also co-counsel in HIA v DEA III, which challenged the DEA's Marijuana Extract Rule for failing to make a carve-out for CBD derived from industrial hemp. The HIA sought to establish a legal distinction between hemp-derived and marijuana-derived CBD. The petition was denied on procedural grounds, but Goggin says the 9th Circuit issued an "unpublished order" finding that the Controlled Substances Act is pre-empted in this matter by the Industrial Hemp Research Amendment of the 2014 Farm Bill. Such unpublished orders do not actually establish case law, but are held to have "persuasive authority." So the case was a moral if not a technical win.

The pending 2018 farm bill would mean full transition to commercial production. Officially the Hemp Farming Act, its language actually removes the word "industrial," thereby "removing arguments against particular uses," Goggin says.

It was the 2014 Farm Bill that made the 0.3% THC limit federal law, following its adoption in several state laws, including Kentucky, Oregon, Colorado and California.

Goggin notes that the European Union, which first established the 0.3% limit in 1984, lowered it to 0.2% in 1999—widely perceived as due to pressure from French producers who sought to retain their market share as such major producers as Hungary moved to join the EU.

"There was no science," Goggin says. "It was based on some group's effort to get a more competitive advantage. It was capitalist."

Canada was also ahead of the US in adopting the 0.3% limit, establishing the standard in 1998 by an act of parliament..

Goggin sees an ecological imperative to raise the limit. "Raising it opens up new cultivars and strains that aren’t able to get down to 0.3. So it gives more flexibility to farmers. We are trying to recover our seed stock, because we didn't grow it from 1958 to 2015. We need cultivars and seed that are adopted to the region they are growing in—for soil and climate and sun exposure."

1958 was the year of the last legal hemp crop in the United States—in Wisconsin. That was before the 1971 Controlled Substances Act, and under the old Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 (which established prohibitive taxes for cannabis), there was a more lenient taxation rate for industrial hemp farmers. The distinction was then based on farming methods (tall hemp densely planted in rows) and end-use, rather than any actual limit on the THC level. Still, the tax was high enough for farmers to abandon the crop, especially in the age of synthetic fibers.

Eric Steenstra of advocacy group Vote Hemp similarly argues that the "practical effect of the 0.3% standard is it limits the types of genetics that can be used." He notes that marijuana sold today can be up to 30 % THC. "So a plant with 1% is ditch-weed" for a toker. "It's garbage."

Steenstra notes that West Virginia went for a 1% limit in 2002..

So how did this all get started?

Food and drug researcher Jace Callaway has been growing his FINOLA brand hemp in Kuopio, Finland, since 1995. Before that he worked at the Department of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Mississippi. In the same building, the School of Pharmacy was doing what Callaway calls its “cop-related” cannabis research—the only cultivation then approved by the DEA, and funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Callaway spoke to Cannabis Now by phone from Winnipeg, where he was attending the Canadian Hemp Trade Alliance annual conference. FINOLA is widely grown in Canada, as well as across Europe. Derived from an "escaped cultivar" (that is, one gone feral after a period of agricultural use) probably of Russian origin, FINOLA is registered with the Geneva-based International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV).

While FINOLA generally falls well below the 0.2% threshold, Callaway emphasizes: "Any hemp variety can be pushed over that limit. It's a question of how it's grown—light, fertilization, harvest time—and how it's sampled. That is, what part of the plant—whole plant or just bud—and how the sample is analyzed, and how competent the lab is."

Callaway also points to pressure from France's National Federation of Hemp Producers (FNCP) as explaining the lower EU standard. And he sees even the 0.3% limit as an inappropriate use of a "taxonomical" standard to make policy..

Callaway says the limit traces back to the work in the 1970s of Ernest Small, a staff researcher with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, the Canadian department of agriculture.

"Ernie Small proposed that number as a taxonomic distinction between THC-rich cannabis and THC-poor cannabis. He never intended this number to be used as an delineation for law enforcement or for reasons of 'public safety,' which is the usual excuse. In fact, if Ernie knew that his suggestion would have been used in this way, then he would have suggested the limit to be 1%."

Callaway said Dr. Small had said as much when he dined with him in Ottawa just a night before. But what does Small himself have to say on the matter?

Ernest Small speaks on his legacy

Dr. Small clearly seems slightly ambivalent about his 0.3% legacy. In his most recent book, Cannabis: A Complete Guide, published by the UK’s Taylor & Francis in 2016, he writes: "A level of about 1% THC is considered the threshold for marijuana to have intoxicating potential, so the 0.3% level is conservative, and some jurisdiction (e.g. Switzerland and parts of Australia) have permitted the cultivation of cultivars with higher levels."

The 0.3% limit was first proposed in a 1976 paper in the Netherlands-based scientific journal Taxon that Small co-wrote with Arthur Cronquist of the New York Botanical Garden, "A Practical and Natural Taxonomy for Cannabis." The text actually stated: "It will be noted that we arbitrarily adopt a concentration of 0.3% Delta9-THC (dry weight basis) in young, vigorous leaves of relatively mature plants as a guide to discriminating two classes of plants." (Emphasis added.).

Reached by phone at his office in Ottawa, Dr. Small had this to say when asked how he felt as his idea was taken up by the policy world: "Initially, quite flattered. Because we in the business of taxonomy try to propose classifications useful to society. Our work was adopted as a criterion to prevent what I’ll call abuse of the euphoric possibilities of the cannabis plant."

But Dr. Small continues: "A 0.3% level is very conservative, and my skepticism today is if we were to adopt a criterion for non-abusive use of the plant—e.g. for oilseed, an important product—I'd suggest 1% as a more reasonable criterion. Because that’s the level you need for a euphoric effect."

He also stresses the implications for biodiversity and sustainability: "Zero point three is proving a little problematical for those who wish to produce some cultivars. It’s an especially stringent criterion those who want to produce CBD. Most of the varieties selected for that have in excess of 0.3, which is kind of inconvenient."

He notes the paradox that ornamental opium poppy is completely tolerated. "There is no such limit in legislation or regulations for ornamental opium. This all reflects a certain inconsistency, ignorance and irrationality of we as human beings. But fear-mongering that becomes established in society and legislation is hard to change."

Small is nonetheless unequivocal: "I've said it in a number of conferences I've attended. A more rational and justifiable standard for THC content in cultivated cannabis should be 1% rather than 0.3 on a dry-weight basis of the flowers and reproductive parts of the plant."

Patrick Goggin also believes that "a standard of 1% probably makes more sense," and is more optimistic on the possibilities for change. "We can start at the state level to build momentum for the federal government to adopt a more lenient threshold," he says. "If you look at our federalist system, the way we've been able to get the feds to act at all on hemp is with pressure from the states."

This story first ran Dec. 20 in Cannabis Now

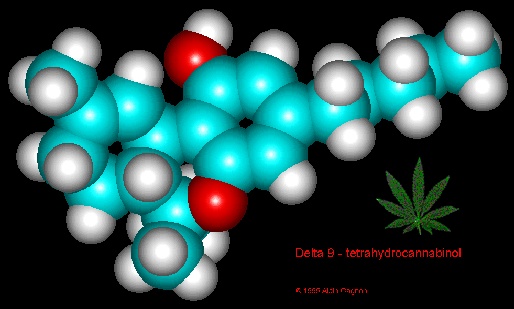

Image of THC molecule via Schaffer Library of Drug Policy

Recent comments

9 weeks 19 hours ago

10 weeks 5 hours ago

11 weeks 4 days ago

12 weeks 20 hours ago

12 weeks 2 days ago

16 weeks 5 days ago

17 weeks 6 days ago

17 weeks 6 days ago

19 weeks 1 day ago

24 weeks 2 days ago