The claim that cannabis causes "mental illness" rears its dubious head like clockwork every few years, and this latest round has occasioned a virtual media frenzy—a seeming backlash to the recent advances in normalization of the herb and its aficionados. Scratching the claims, however, reveals more hype than rigor.

The claim that cannabis causes "mental illness" rears its dubious head like clockwork every few years, and this latest round has occasioned a virtual media frenzy—a seeming backlash to the recent advances in normalization of the herb and its aficionados. Scratching the claims, however, reveals more hype than rigor.

The headlines are all too familiar ones, but this time they got very prominent play.

Former New York Times reporter Alex Berenson ran an op-ed in that newspaper Jan. 4, "What Advocates of Legalizing Pot Don't Want You to Know." The kicker: "The wave toward legalization ignores the serious health risks of marijuana." His claims have been picked up by The New Yorker and even progressive media organs like Mother Jones. One wishes these write-ups had examined Berenson's work with a more critical eye.

Countervailing evidence ignored

Berenson's most damning claim is that evidence links cannabis use to "mental illness." We've heard such assertions many times before, but Berenson portrays an emerging medical consensus.

He notes that in a 1999 report, the Institute of Medicine wrote that "the association between marijuana and schizophrenia is not well understood," and even suggested that cannabis might help some people with schizophrenia. But in 2017, the Institute's successor organization, the National Academy of Medicine, issued a new study, finding: "Cannabis use is likely to increase the risk of schizophrenia and other psychoses; the higher the use, the greater the risk."

Sounds damning. But if you actually examine the NAM report (entitled "The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research"), it becomes clear that Berenson is distorting things.

For starters he quotes that line as the report's "conclusion." In fact, it is one of several "chapter highlights" in the report, and reviewing the list reveals that Berenson cherry-picked the most damning. Among these he did not cite: "In individuals with schizophrenia and other psychoses, a history of cannabis use may be linked to better performance on learning and memory tasks." And: "Cannabis use does not appear to increase the likelihood of developing depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder."

The phrase actually listed as a "conclusion" of the report (not quoted by Berenson) is more cautious: "There is substantial evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and the development of schizophrenia or other psychoses, with the highest risk among the most frequent users."

Note that a "statistical association" does not necessarily imply causality. The discussion leading up to this "conclusion" is full of caveats, such as: "[T]he relationship between cannabis use and cannabis use disorder, and psychoses may be multidirectional and complex." And: "[I]t is noteworthy to state that in certain societies, the incidence of schizophrenia has remained stable over the past 50 years despite the introduction of cannabis into those settings..."

This last point is particularly critical. Worldwide rates of schizophrenia have remained constant since the 1950s despite dramatic increases in the use of cannabis, especially in Western countries. This reality was documented in a 2009 study by researchers at Britain's Keele University Medical School published in the journal Schizophrenia Research, "Assessing the impact of cannabis use on trends in diagnosed schizophrenia in the United Kingdom from 1996 to 2005."

In 2008, as that study was being prepared, its authors handed preliminary findings in to the British government's Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. The Guardian reported: "Their confidential paper found that between 1996 and 2005 there had been significant reductions in the incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia. From 2000 onwards there were also significant reductions in the prevalence of psychoses. The authors say this data is 'not consistent with the hypothesis that increasing cannabis use in earlier decades is associated with increasing schizophrenia or psychoses from the mid-1990s onwards.'"

In fact, based on these findings, if we are to assume causality at all (always a tricky proposition), cannabis use may be beneficial to mental health!

To return to Berenson's text... He does cite a statistical increase that on first read seems like cause for concern: "According to the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in 2006, emergency rooms saw 30,000 cases of people who had diagnoses of psychosis and marijuana-use disorder—the medical term for abuse or dependence on the drug. By 2014, that number had tripled to 90,000."

However, this does not mean there was an increase in cases of psychosis—only in cases of psychosis accompanied by "marijuana-use disorder"—itself a condition usually defined in circular, question-begging ways (e.g., the National Institute on Drug Abuse calls it "problem use"). If cases of psychosis, with or without "marijuana-use disorder," remained constant or decreased, that would merely indicate an increase in the latter—not any link between the two, much less a causative one.

Berenson goes on the state: "Federal surveys also show that rates of serious mental illness are rising nationally, with the sharpest increase among people 18 to 25, who are also the most likely to use cannabis." Yeah well, people in that age group are also just entering the job market, typically with no or little savings, at a time of uncertainty since the 2008 financial crash and subsequent "jobless recovery." If this rising "mental illness" includes severe anxiety, there might be very good reason for it. But we're not supposed to talk about that.

Reefer Madness recycled

Berenson goes on to recycle some other cannabis calumnies that have already been pretty well debunked.

For instance, the high potency bugaboo. Berenson writes: "Many older Americans remember marijuana as a relatively weak drug that they used casually in social settings like concerts. They're not wrong. In the 1970s and 1980s, marijuana generally contained less than 5 percent THC. Today, the marijuana sold at legal dispensaries often contains 25 percent THC. Many people use extracts that are nearly pure THC. As a comparison, think of the difference between a beer and a martini."

This betrays a real misunderstanding of the whole question. Back in 2016, when Canada was debating whether or not to adopt a THC maximum for legal cannabis, Hilary Black of the BC Compassion Club Society told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation: "With a potent cannabis strain, somebody may have just one or two little puffs of their vaporizer and that's it. In many ways more potent strains of cannabis can be healthier to use." On the basis of this logic, Canadian health authorities rejected a THC maximum for herbaceous cannabis.

"I am not a prohibitionist," Berenson protests, saying he supports decriminalization rather than legalization—before going on to dredge up more prohibitionist talking points.

"[B]ecause marijuana can cause paranoia and psychosis, and those conditions are closely linked to violence—it appears to lead to an increase in violent crime," he writes. "Before recreational legalization began in 2014, advocates promised that it would reduce violent crime. But the first four states to legalize — Alaska, Colorado, Oregon and Washington—have seen sharp increases in murders and aggravated assaults since 2014, according to reports from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Police reports and news articles show a clear link to cannabis in many cases."

Note several problems here. First, Berenson tells us cannabis "can cause" psychosis, after the study he cited used far more cautious language. Even if he had written "may cause" it would have been a bit of a stretch; "can cause" is downright irresponsible. Then, as a refreshingly skeptical look at his work in New York Magazine notes, the FBI stats indicate a national uptick in violent crime since 2014—so Berenson is being dishonest by only citing the states that have legalized. He also fails to cite any legalization advocates who "promised" a reduction in violent crime—which would have been a foolish pledge, as outcomes may be influenced by factors unrelated to cannabis. Finally, he fails to define the "clear link" to cannabis. Again: if a perpetrator toked before an assault, does that imply causality? No. The rumor-busters at Snopes examine the claim that "Marijuana legalization has led to an increase in crime and fatalities all over Colorado." Thier finding? "Unproven." They also examine this claim: "There is a demonstrable link between marijuana legalization and an increase in violent crime." Their finding? False.

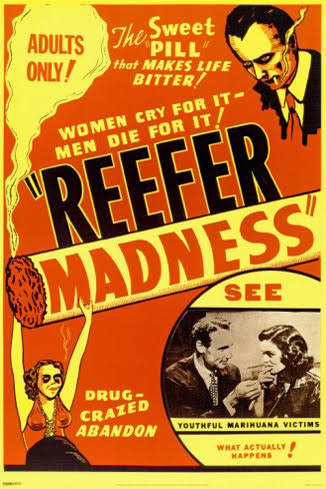

In an ironic line, Berenson protests: "[L]egalization advocates have squelched discussion of the serious mental health risks of marijuana... As I have seen firsthand in writing a book about cannabis, anyone who raises those concerns may be mocked as a modern-day believer in 'Reefer Madness,' the notorious 1936 movie that portrays young people descending into insanity and violence after smoking marijuana. "

Yet the claims Berenson is peddling are not too far removed from those 1930s propaganda chestnuts. And his upcoming book is entitled Tell Your Children: The Truth About Marijuana, Mental Illness, and Violence. As the libertarian blog Reason recalls, "Tell Your Children" was actually the original title of the notorious 1936 propaganda film Reefer Madness!

Berenson's complaint about being painted as a peddler of "Reefer Madness" propaganda brings to mind the famous line from Hamlet: Methinks he doth protest too much.

Cross-post to Cannabis Now

Graphic: Wikipedia

Comments

Alex Berenson compares pot to Chernobyl. Yes, really.