Among the multiple grim challenges facing humanity at this moment is the specter of "antibiotic apocalypse"—so-called "superbugs" developing resistance to common antibiotics, portending a plague of incurable infections. Research in Australia now reveals anti-bacterial properties in CBD, effective even against the growing ranks of resistant superbugs. Many in the stateside cannabis industry say the development is further evidence that legal barriers to research need to come down—and fast.

Among the multiple grim challenges facing humanity at this moment is the specter of "antibiotic apocalypse"—so-called "superbugs" developing resistance to common antibiotics, portending a plague of incurable infections. Research in Australia now reveals anti-bacterial properties in CBD, effective even against the growing ranks of resistant superbugs. Many in the stateside cannabis industry say the development is further evidence that legal barriers to research need to come down—and fast.

Amid all the utopian sensationalism about the supposedly salubrious properties of the newly legal cannabinoid CBD, some are developing a skeptical attitude toward the newest amazing claims. But the latest, among the most ambitious we've yet heard, really are attracting serious attention from the medical establishment. New research has revealed antimicrobial properties to CBD—and even potential for outsmarting the antibiotic-resistant "superbugs" now vexing the scientific community.

The researchers in Australia found that CBD killed all strains of bacteria tested in a laboratory—including some that have developed resistance to existing antibiotics. Even more encouragingly, the bacteria did not develop resistance to CBD after being exposed to it for 20 days. This means CBD may be able to outmaneuver the entire process by which superbugs develop.

A 'unique mechanism'

The experiment was carried out by the Centre for Superbug Solutions at the University of Queensland's Institute for Molecular Bioscience. Researchers tested a group of bacteria called Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus—also dubbed the MRSA Suprebug, for Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Methicillin is a penicillin-based antibiotic once widely used but now being phased out because it is no longer effective against pernicious new breeds. So-called Gram-positive bugs are those with a particularly thick cell-wall.

The team also tested Streptococcus pneumoniae and E. faecalis, both of which can be life-threatening for those with compromised immune systems.

Team leader Mark Blaskovich admitted to Newsweek, "We still don't know how it works... [I]t may have a unique mechanism of action given [that] it works against bacteria that have become resistant to other antibiotics, but we still don't know how."

The study was funded by the Australian government and Botanix Pharmaceuticals, a Perth-based company that is researching uses of CBD for treating skin conditions. The findings were presented at the American Society for Microbiology's Microbe 2019 conference in San Francisco in June. The findings have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

So the research, as promising as it seems, is in the early stages. Newsweek sensibly asked Blaskovich for his advice for those who might ditch standard antibiotics for cannabis-based home remedies. He responded unequivocally: "Don't! Most of what we have shown has been done in test tubes—it needs a lot more work to show it would be useful to treat infections in humans."

At this stage, "it would be very dangerous to try to treat a serious infection with cannabidiol instead of one of the tried and tested antibiotics," he stressed.

Nonetheless, CBD may be providing a first glimmer of hope in a dilemma with deeply troubling implications for the future of the human race.

Medical establishment paying attention

The study has won interest from the medical establishment, with a flurry of coverage in both popular and trade journals since the San Francisco unveiling.

The researchers looked at how effective CBD was compared to common antibiotics, such as vancomycin (marketed as Vancocin) and daptomycin—to very positive results. "We looked at how quickly the CBD killed the bacteria. It's quite fast, within three hours, which is pretty good. Vancomycin kills over six to eight hours," Blaskovich told WebMD

CBD was found to disrupt biofilm, the layer of "goop" (WebMD's word) around bacteria cells that makes it difficult for antibiotics to penetrate and kill. Results showed that "CBD is much less likely to cause resistance than the existing antibiotics," Blaskovich said.

In another caveat, he told WebMD that CBD "is selective for the type of bacteria." It was found to be effective against Gram-positive bacteria but not Gram-negative. Gram-positive strains cause serious skin infections and pneumonia, among other conditions. Gram-negative types include salmonella and E. coli, more associated with gastrointestinal disorders.

WebMD turned to scientists not involved in the research for their reactions. Brandon Novy, a microbiologist at Reed College in Portland, Ore., called the findings '"very promising."

"It is an important study that deserves to be followed up on," added Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

An optimistic headline in Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News read: "CBD as a Next-Gen Antibiotic."

This account noted that the study used lab-synthesized CBD, not that actually derived from cannabis. "We assessed the antimicrobial activity of synthetically produced cannabidiol, free from isolation-dependent impurities that may confound biological testing results obtained with plant extracts," Blaskovich and his co-authors wrote. "Cannabidiol was tested in a suite of standard antimicrobial assays, starting with broth microdilution assays against a range of aerobic and anaerobic Gram-positive bacteria."

Unlocking potential of cannabinoids

Among the stateside companies enthused by the antimicrobial potential of CBD is EcoGen Laboratories of Grand Junction, Colo. With 160,000 square feet of greenhouse cultivation, EcoGen is a major source of the CBD isolate and distillate found in products available in retail outlets nationwide. It is also providing isolate, distillate and plant samples to researchers at UCLA and other universities.

EcoGen chief growth officer Derek Du Chesne told Cannabis Now he hopes that the promising claims of the Australian study will help break down the barriers to research in the United States. "We would love to supply them cannabinoids and material they will need to develop CBD antibiotics," he says.

Du Chesne rattles off various established applications of CBD—for instance, it is already being used in dental offices as a supplemental anti-inflammatory treatment. But he also urges research into the pharmacological value of the "lesser known cannabinoids."

He mentions cannabicyclol (CBL), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabichromene (CBC) and cannabinol (CBN) as holding possibilities for similar breakthroughs.

Du Chesne calls CBG the "next one in the spotlight" for its anti-inflammatory value. CBN research shows potential for cancer-fighting, sleep-aiding and anti-seizure applications. Du Chesne acknowledges that CBN is difficult to extract, and is only found in trace amounts in the plant. "But extraction technology is improving," he says.

A freer legal environment also helps to make extraction of such cannabinoids more viable. "Four years ago, CBD isolate went for $20,000 a kilo. Now it's $2,000 a kilo due to the supply chain being freed up by the Farm Bill." CBG now goes for $30,000 a kilo, half what it was last year.

"Most cannabis research over last 20 years has come out of Israel," Du Chesne says. "In the US, it is primarily UCLA tha it has been looking at it, and they've had to get their material from the DEA—and it was the lowest-quality imaginable." UCLA's Cannabis Research Initiative is a likely candidate to examine CBD's antiboitic properties.

"There's been a lot more money put toward suppressing the research than toward the research," Du Chesne notes. "The science hasn't caught up with the market, Now that the raw material is available and the restrictions on the research are going down, it is going to affect the pharmaceutical business in a very large-scale way."

Cross-post to Cannabis Now

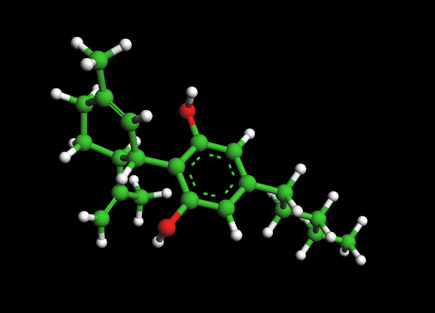

Image: World of Molecules

Recent comments

6 weeks 1 day ago

6 weeks 1 day ago

9 weeks 2 days ago

10 weeks 1 day ago

14 weeks 2 days ago

18 weeks 13 hours ago

22 weeks 18 hours ago

22 weeks 6 days ago

32 weeks 6 days ago

36 weeks 6 days ago