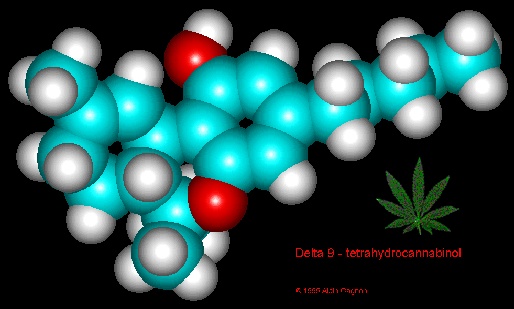

CBD products are now everywhere—health-food emporia, pharmacies, truck-stops. And pursuant to the 2018 Farm Bill, they are now legal—as long as the CBD is derived from “hemp” as opposed to what has traditionally been called “marijuana.” Hemp, as legally defined, is cannabis with under 0.3% THC—the psychoactive component of the plant, responsible for the long-stigmatized “high.”

CBD products are now everywhere—health-food emporia, pharmacies, truck-stops. And pursuant to the 2018 Farm Bill, they are now legal—as long as the CBD is derived from “hemp” as opposed to what has traditionally been called “marijuana.” Hemp, as legally defined, is cannabis with under 0.3% THC—the psychoactive component of the plant, responsible for the long-stigmatized “high.”

But even the hempiest hemp—rope, not dope, as they used to say—usually has some THC.

So after the process of CO2 extraction, further refinement with ethanol or liquid chromatography, and final production of CBD distillate or isolate, there is going to be some THC left over. For what is called “full spectrum” distillate, the final product will include terpenes, essential oils and even other cannabinoids—but not THC, if it is to be legally marketed. Once the spectrum is narrowed to legal limits it is generally designated "broad" rather than "full."

“Broad spectrum” distillate may still include some THC, but within the 0.3% limit—which still means there will likely be some left over. For isolate, THC as well as the terpenes and other cannabinoids will be considered waste products, ostensibly to be disposed of.

Panacea Life Sciences, a Colorado company specializing in full-spectrum oil products, was queried on what the protocol is for the leftover THC. “We can’t do anything with it because it’s illegal,” says Panacea’s controller Nathan Berman. “We contract a company that picks up the waste material and destroys it.”

A little more detail is provided by another Colorado CBD extractor, Folium Biosciences. Liz Wilkinson, director of marketing at the Colorado Springs firm, says: “We contract a third-party hazmat company to come every Friday to take the THC and mix it with agent that makes it unrecognizable and essentially useless. And then they take it offsite and dispose of it.”

“Hazmat” of course is short for “hazardous materials.” But the identity of the contracted company? Wilkinson will only say: “They are a certified hazmat company. I can’t share name of the company because we have a non-disclosure agreement with them.”

Panacea does offer that the chemical agent in question is pentane, a flammable hydrocarbon akin to butane and hexane.

THC, of course, is actually legal in Colorado—when it is in the regulated adult-use market. But most states that have legalized, including the Centennial State, maintain a legal firewall between CBD or hemp producers and “recreational” (read: psychoactive) cannabis. That is, no diversion of the THC “waste” into the regulated marijuana market is allowed.

One partial exception is Oregon. There, THC “waste product” with concentration limits up to 5% may be sold under the regulated market overseen by the Oregon Liquor Control Commission (OLCC). This was permitted by the Beaver State’s Health Bill 4089 of 2018.

Now, 5% still isn’t enough to get you high, but it can be used in conjunction with CBD for those who seek the “entourage effect” of the true “full spectrum” experience.

Courtney Moran, an attorney specializing in hemp and cannabis with the Portland firm EARTH Law, says, “A lot of people would like to see that 5% increased. But the regulated marijuana system overseen by the OLCC has limits on canopy which do not apply to hemp.”

So even in Oregon, the legal firewall still exists—it just has a limited exception.

However, an inevitable question presents itself: is some of this THC “waste product” being illegally diverted, either to the regulated market or the illicit market?

One industry insider who smells this particular rat is Jerry Whiting, Seattle-based “négociant-éleveur” (merchant-breeder, a term borrowed from the wine industry) with LeBlanc CNE, which offers CBD products and is also developing a seed bank for high-CBD strains.

“Two things can lead to diversion,” Whiting says. “First, if you’re actually growing marijuana under hemp license, the inspectors say you have to burn it. But they don’t stick around to see if you do, so it gets diverted to black market. Then there’s production of CBD raw isolate or distillate. There are extractors who look at the waste material as a business opportunity. If there’s a front door there’s a back door, and if you’re a good enough chemist to extract CBD you can extract THC.”

Meaning the THC can be isolated from the rest of the stuff in the waste, and sold profitably—if not legally.

“There are instances where things are not flushed down the toilet,” Whiting asserts. “They are going into illicit-market vape carts. And sometimes they’re adding vitamin E to stretch the THC, to sell 20 or 30 more cartridges.”

Vitamin E acetate is one of the adulterants identified as a possible culprit in the wave of pulmonary illness associated with vaping, now responsible for over 30 deaths from coast to coast. This is simply the oil form of the vitamin, and perfectly legal—indeed, salubrious—when ingested or used topically, but apparently hazardous when inhaled.

Whiting sees such diversions to irresponsible actors as an inevitability. “There’s someone who's gonna buy whatever you grow or whatever you come out of a lab with, and its untraceable money so it isn’t taxed. There’s a whole shadow processing ecosystem.”

It’s important to keep in mind that it’s the continued illegality of “recreational” cannabis in all but 10 states that incentivizes this kind of anti-social hanky-panky. Until there is legalization at the federal level and a regulated interstate market, the temptation of THC diversion will likely persist.

This story first ran Feb. 19 on Project CBD

Image of THC molecule via Schaffer Library of Drug Policy

Recent comments

5 weeks 6 days ago

5 weeks 6 days ago

9 weeks 45 min ago

9 weeks 6 days ago

13 weeks 6 days ago

17 weeks 5 days ago

21 weeks 5 days ago

22 weeks 3 days ago

32 weeks 3 days ago

36 weeks 3 days ago