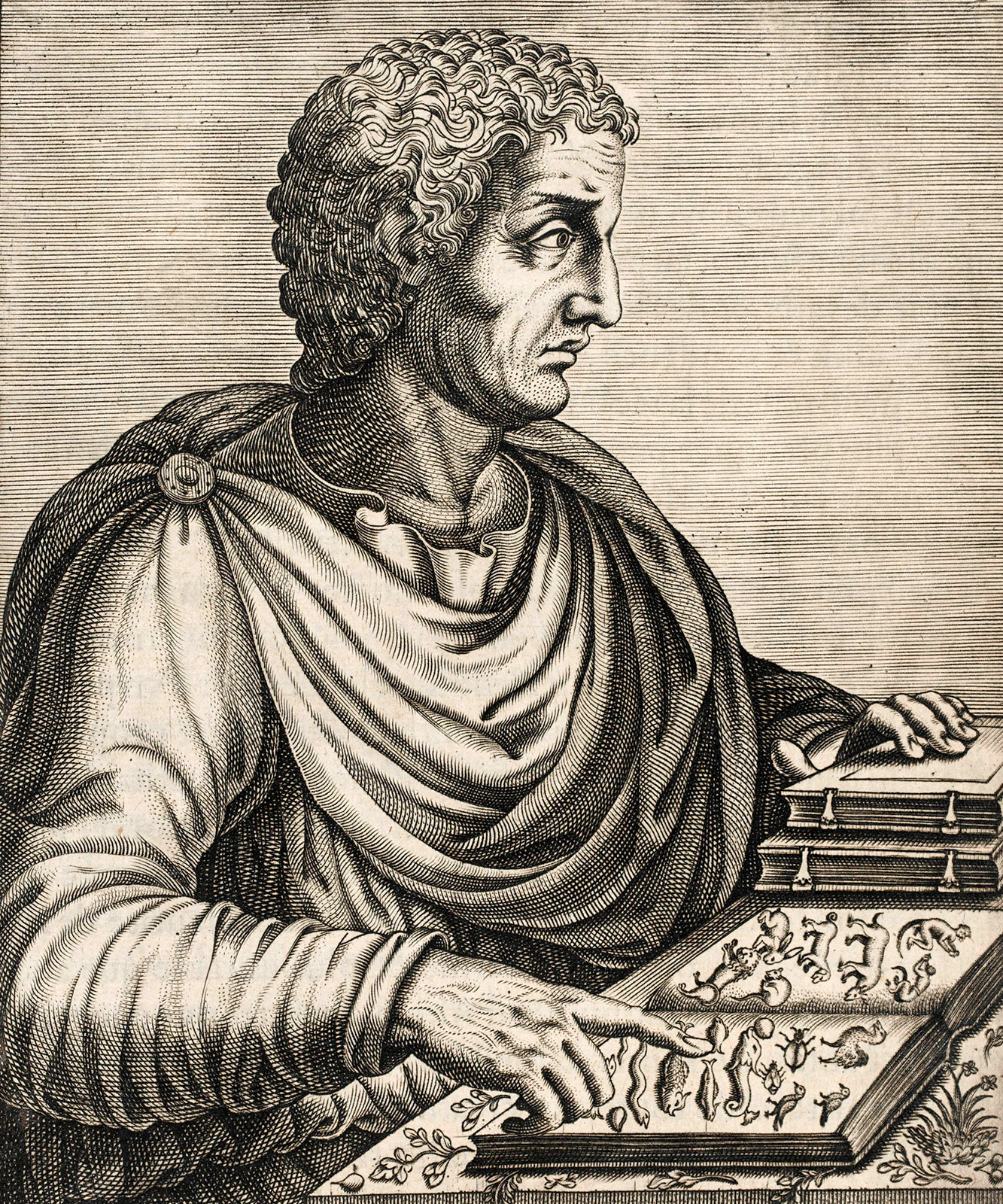

An esteemed scholar and writer from ancient Rome recently re-emerged in the news with reports that a forensic study confirmed claims that his skull had been found. Historians of the cannabis plant have long contended that Pliny the Elder was among the first to make note of its curative and psychoactive properties.

An esteemed scholar and writer from ancient Rome recently re-emerged in the news with reports that a forensic study confirmed claims that his skull had been found. Historians of the cannabis plant have long contended that Pliny the Elder was among the first to make note of its curative and psychoactive properties.

It's rare when news headlines concern someone who died nearly 2,000 years ago. But that’s what happened last month, when a scientific team in Italy reported results of their study—finding that the skull in a Rome museum really is that of Pliny the Elder, the immortal naturalist of the ancient Roman world.

As the New York Times related, the skull had been sitting for decades in the Museo Storico Nazionale Dell'Arte Sanitaria, or National Historical Museum of Medical Arts, described as a "treasure trove of medical curiosities." It had been unearthed in an excavation in 1900 on the shore of the Bay of Naples near the ruins of Pompeii, along with some Roman-era jewelry and regalia. As Pliny was killed in the 79 CE eruption of Mount Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii, and was said to have met his death on that fabled shoreline, there was inevitably speculation.

The landowner who discovered the skull seems to have leveraged it for personal notoriety as the man who found the remains of Pliny. After changing hands a few times, it wound up in the museum some 70 years ago—first plugged as "Pliny the Elder's skull," then, less ambitiously, as "Skull from the excavations of Pompeii and attributed to Pliny."

The forensic study, which was launched in 2017, used DNA sequencing and an analysis of cranial shape to determine that the skull fits what we know from history about Pliny's general profile. Andrea Cionci, leader of the study, dubbed Project Pliny, told the Times: "It is very likely that the skull is Pliny, but we cannot have 100% security. We have many coincidences in favor, and no contrary data."

The identity of the skull remains a matter of some controversy. The Times ironically quoted a line from Pliny himself: "In these matters, the only certainty is that nothing is certain."

There is, however, a greater degree of certainty about Pliny's role as one of history's first scholars to document the medicinal properties of the cannabis plant.

Admiral, adventurer, naturalist

Gaius Plinius Secundus, born around 23 CE, led military campaigns for Imperial Rome in Germany before being assigned as a naval admiral in the Bay of Naples to fight piracy. In between such adventures he wrote his classic work, Naturalis Historia, or Natural History (sometimes rendered in the plural as Naturae Historiae).

Natural History was, in the words of one historian, a "compendium of ancient knowledge and misinformation." Amid a massive 37-volume review of flora and fauna from across what was for Rome the known world are such fanciful creations as griffins and cyclopes. But it was the first such compendium of its kind in the Western world, and became the standard reference work throughout the Middle Ages.

And his intellectual curiosity seems to have played a role in his demise. This episode was recorded in letters by his nephew and adopted son, who witnessed it and survived. This was Pliny the Younger, then 17, who would go on to become a statesman, serving as governor of Bithynia in Asia Minor (contemporary Turkey).

From his command post on the Bay of Naples, uncle and nephew witnessed a giant cloud rising from Mount Vesuvius.

"Having seen the cloud, Pliny the Elder decided he wanted to get closer to it to investigate," Daisy Dunn, author of the Pliny biography The Shadow of Vesuvius, told the New York Times. "He was, after all, author of a 37-volume book of natural history."

But as his ship crossed the bay toward Pompeii, it became clear that many were trapped on the shore as lava descended on the city from the volcano and ash rained down from the sky. According to another work on Pliny—Indagine sulla Scomparsa di un Ammiraglio, or Inquiry on the Death of an Admiral, by military historian Flavio Russo—what began as a personal investigation of a natural phenomenon became "the oldest natural disaster relief operation."

It was, alas, in vain. By the time his craft had reached the stricken shore, Pliny the Elder had asphyxiated to death on the toxic fumes.

Pliny and the pharmacopeia of cannabis

Despite the dubious or fantastical elements of his work, Pliny has had a huge influence. As Daily Beast notes, some have speculated that he even helped inspire Charles Darwin, a member of the Plinian Society, to develop his theory of inheritable traits.

His influence on the pharmacopeia of cannabis has only recently come to be recognized, and may also be considerable.

There are numerous references in the Natural History to what English translators have rendered as "hemp." Pliny clearly makes note of its industrial applications, calling it "a plant remarkably useful for making ropes."

The footnotes for the hemp references in the most authoritative translation, by British scholar John Bostock, published in 1856, read: “The Cannabis sativa of Linnæus.” This is a reference to Carl Linnaeus, the 18th century Swedish botanist known as the father of modern taxonomy, who invented the system of plant classification still in use today.

Given that the Latin word for hemp is cannabis, there is little controversy here.

The likely references to medicinal and ecstasy-inducing ("recreational," in contemporary parlance) use of the plant are somewhat more ambiguous.

In his book Cannabis and the Soma Solution, the Canadian chronicler of ancient cannabis use Chris Bennett notes that Pliny cited references in an earlier work by the Greek philosopher Democritus (c. 460—c. 370 BCE), himself the central figure in development of the atomic theory of the universe (dramatically vindicated by science in the 20th century).

The lost earlier work by Democritus made note of an herb called theangelis that "grows upon Mount Libanus in Syria" (contemporary Lebanon), and "at Babylon and Susa in Persia." Democritus, in a passage quoted by Pliny, wrote: "An infusion of it imparts powers of divination to the Magi." The Magi, of course, were the sages and priests of the ancient Persian religion, Zoroastrianism.

Pliny also noted Democritus’ reference to geolotophyllis, "a plant found in Bactriana" (contemporary Afghanistan) and "on the banks of the Borysthenes" (the Dnieper River, in contemporary Russia and Ukraine). "Taken internally with myrrh and wine, all sorts of visionary forms present themselves, excite the most immoderate laughter."

As Bennett notes, Bostock's footnotes for both these esoteric terms identified them as "Indian hemp, cannabis sativa."

Christian Rätsch in his Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants lists theangelis and geolotophyllis in his section "Psychoactive Plants That Have Not Yet Been Identified." However, Pliny's geographic references are in line with what we know about the origin of the cannabis plant in Central Asia (the Tibetan plateau, by the most recent research), and its diffusion from there across the steppes to Europe and the Middle East.

This makes Pliny one of the earliest writers to mention cannabis use—although earlier ones include the Greek historian Herodotus, who noted its use by the Scythians, and the herbal compendiums in India's Athrava Veda and the Pen Ts'ao of the legendary Chinese emperor Shen Nung (c. 2800 BCE).

On a less esoteric tip, Pliny also noted that an infusion of cannabis root boiled in water "eases cramped joints, gout too, and similar violent pain." He also recommended hemp seed oil as a treatment for ear infections ("worms").

This was noted in the December 2017 edition of the peer-reviewed quarterly journal Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, in an article entitled "Cannabis Roots: A Traditional Therapy with Future Potential for Treating Inflammation and Pain."

The article, written by a team led by Vancouver physician and cannabis therapeutics pracitioner Natasha R. Ryz, stated: "In the first century, Pliny the Elder described in Natural Histories that a decoction of the root in water could be used to relieve stiffness in the joints, gout, and related conditions. By the 17th century, various herbalists were recommending cannabis root to treat inflammation, joint pain, gout, and other conditions."

Although the plant's root contains few cannabinoids, this points to a link between Pliny and the later medicinal use of cannabis tinctures and the like in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This tradition came to an abrupt halt in the United States with federal prohibition in 1937, and has only been rediscovered since the emergence of the medical marijuana movement a little more than a generation ago.

The works of Pliny the Elder certainly demonstrate that cannabis use is not some recent innovation, but deeply rooted in human culture.

Cross-post to Cannabis Now

Image: britannica.com

Recent comments

5 weeks 2 days ago

5 weeks 3 days ago

8 weeks 3 days ago

9 weeks 3 days ago

13 weeks 3 days ago

17 weeks 1 day ago

21 weeks 2 days ago

22 weeks 9 hours ago

32 weeks 9 hours ago

36 weeks 19 hours ago