Researchers are exploring the connection between cannabinoids and dopamine in the human brain, and particularly how THC affects our "reward system"—key to such phenomena as motivation, addiction and euphoria. Investigations are revealing both potential for treatments of psychiatric disorders as well as possible risks from heavy use, especially among the young.

Researchers are exploring the connection between cannabinoids and dopamine in the human brain, and particularly how THC affects our "reward system"—key to such phenomena as motivation, addiction and euphoria. Investigations are revealing both potential for treatments of psychiatric disorders as well as possible risks from heavy use, especially among the young.

The cannabis plant contains over 100 different cannabinoids, each interacting with the human brain in a specific way. Researchers are increasingly focusing on the key role dopamine plays in those interactions.

This is not surprising, as dopamine is critical to the brain's "reward system," which plays a key role in motivation, by "rewarding" us with a euphoric kick—or, in its negative role, denying us that kick. This, in turn, makes dopamine key to understanding addiction and other behavior patterns identified as pathological, such as depression.

This research may shed light on the recent string of much-hyped claims linking cannabis use to "psychosis and schizophrenia"—and what the actual risks, and potential benefits, really are.

Cannabinoids as 'anti-psychotic' treatment

Recent research has looked to cannabinoids as possible treatments for psychiatric disorders. And like most such treatments, this has to do with the impact on how dopmaine is produced and transmitted in the brain.

An August article in Medical Life Sciences News states: "Traditional antipsychotics are thought to work by targeting the release of certain neurotransmitters in the brain, namely noradrenaline, acetylcholine, serotonin, and most notably, dopamine. The dopamine hypothesis, which has dominated psychosis treatment to date, postulates that an excess of dopamine in the brain causes psychotic symptoms."

"Anti-psychotic" medications now in use bind to dopamine receptors, thus reducing dopamine production. Cannabinoids are being explored as alternative treatments for patients who do not respond to to the traditional "anti-psychotics."

Once again, it is noted that THC and CBD appear to have contradictory effects that balance each other out to a degree: "THC activates CB1 receptors within the brain, causing feelings of euphoria, but CBD is an antagonist at the CB1 receptors..."

CBD is particularly looked to as a possible "new class of treatment for psychosis." Citing recent studies, the report finds: "When the effects of CBD as an adjunct to conventional antipsychotic medication are examined, modest improvements are found on cognition and the impact of patients’ illness on their quality of life and global functioning."

But if CBD is chilling your dopamine out, THC is flooding your neuroreceptors with the stuff—at least initially.

Long-term brain changes?

The same cannabinoid-dopamine link that holds hope for new treatments may also point to risks for heavy cannabis users, especially those whose brains are still developing. A 2017 study by researchers at Utah's Brigham Young University, published in the journal JNeurosci, found evidence that long-term use may in fact change the brain.

The study focused on the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a region of the brainstem identified as one of the two most important clusters of dopamine receptors (the other is the adjacent substantia nigra). The researchers examined how the VTA's cells changed in adolescent mice that received a week of daily THC injections. They compared the results on normal mice and "CB1 knockout mice"—that is, those genetically tweaked to disable their CB1 receptors. They especially looked for impacts on so-called GABA cells. GABA cells (for gamma-aminobutyric acid, the type of neurotransmitter these cells pick up) is known to have an inhibitory effect on "dopaminergic" activity—basically, activity related to dopamine.

The findings determined that "THC acutely depresses GABA cell excitability"—which actually means that the inhibitory effect is depressed, with more dopamine giving you that sought-after buzz. "This suggests that persistent, long-term THC exposure can modify...VTA GABA cells of juvenile-adolescent age mice that may contribute too some of the long-term consequences of marijuana use."

Here the team postulates a clue to the brain mechanism behind what is called "cannabis use disorder"—defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 as a "problematic pattern of cannabis use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress."

Of course, critics have pointed out that such categories are inherently question-begging: Is the "impairment or distress" actually caused by the cannabis use, or are people who suffer from such "impairment or distress" for unrelated reasons self-medicating (consciously or not) with cannabis? If the latter, cannabis use may actually be having a positive, therapeutic effect on sufferers, and the theorists of "cannabis use disorder" may be reading things precisely backwards.

Nonetheless, a write-up on the Birgham Young findings on the pop-science website Inverse, looking for a celebrity news hook, noted that actor Woody Harrelson and singer Miley Cyrus had both recently given up pot, citing adverse reactions. "It's not clear whether Harrelson and Cyrus had been diagnosed with cannabis use disorder, but their reasons for quitting weed seem to line up," Inverse wrote.

The cannabis 'jones'... all about the dopamine

The evidence for a cannabinoid-dopamine link has been mounting for some time. What exactly the link is, and what it means for long-term users, is not yet clear.

A 2016 British study on the website of the National Center for Biotechnology Information found that "the available evidence indicates that THC exposure produces complex, diverse and potentially long-term effects on the dopamine system including increased nerve firing and dopamine release in response to acute THC and dopaminergic blunting associated with long-term use." This suggests an immediate buzz from "increased nerve firing," but diminishing returns as dopamine production is "blunted" (no pun intended, we may presume). This is a pattern that may seem familiar to many long-term users.

A paper entitled "A Brain on Cannabinoids: The Role of Dopamine Release in Reward Seeking," published in 2012 by Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, reviewed several recent studies to postulate a cause for "cannabis-withdrawal syndrome.” Several symptoms of this supposed syndrome are listed, including "anxiety/nervousness, decreased appetite/weight loss, restlessness, sleep difficulties including strange dreams, chills, depressed mood, stomach pain/physical discomfort, shakiness, and sweating." This all may seem rather overstated, but it is plausible that cannabis creates its craving ("jones," in old hispter lingo) by monkeying with the dopamine-regulated reward system. "It is likely," the paper concluded, "that these withdrawal symptoms contribute to cannabis dependence through negative reinforcement processes."

A page on "cannabis aversion" at the website of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), citing research by the Beijing Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, states: "THC's effects on mood derive from its inhibition of two types of neurons that regulate how much dopamine is released into the brain's reward center." One of those is the GABA cells already noted. The other class are the glutamatergic (glutamate-releasing) neurons in the VTA. When the GABA neurons are inhibited, you get that pleasant dopamine rush. When the glutamatergic cells are inhibited, your brain is deprived of glutamate—which, akin to dopamine, is associated with pleasure, and closely interacts with it. In fact, "glutamatergic neurons stimulate the dopaminergic neurons to release dopamine into the brain's reward center." So less glutamate also means less dopamine firing through your brainstem. This dual effect may explain why some people enjoy cannabis and others do not: "Whether the drug is experienced as rewarding or aversive depends in large part on which of the two neuron types is inhibited more." And this can vary from organism to organism. "As a result, when a person is exposed to THC, the experience can be rewarding, aversive, or neutral."

Some skepticism warranted

How this research is applied and interpreted by the psychiatric establishment definitely demands some critical scrutiny, given the long-entrenched prejudice against cannabis, and bias in favor of prescription pharmaceuticals.

In 2014, numerous media reports (both American and British) touted a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences purporting to link cannabis use to anxiety and depression. The researchers studied the brains of 24 cannabis "abusers"—defined as those who smoke multiple times a day—and how they reacted to methylphenidate (more commonly known as Ritalin), a stimulant used to treat hyperactivity and attention-deficit disorder. The study found the "abusers" had "blunted" behavioral, cardiovascular and brain responses to methylphenidate compared with control participants. The "abusers" also scored higher on negative emotional reactions. The researchers concluded that cannabis interferes with the brain's reaction to dopamine.

Mitch Earleywine, professor of psychology at SUNY Albany, speaking to this reporter at the time, raised the same questions about possible confusion of cause and effect in such studies. "I think that giving folks Ritalin or any other stimulant in an effort to assess dopamine release says little if anything about how cannabis users would respond to natural sources of reinforcement," Earleywine said. "These people also weren't randomly assigned to use cannabis, so we have no idea if the altered dopamine reaction preceded or followed cannabis use. Finally, I think if any Big Pharma product did the exact same thing in the lab, we'd be reading about how it protected people against the addictive potential (and induced dopamine release) associated with Ritalin or other stimulants."

Cross-post to Cannabis Now

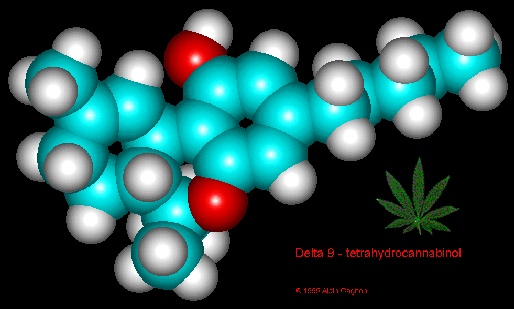

Image of THC molecule via Schaffer Library of Drug Policy

Recent comments

4 weeks 1 day ago

4 weeks 1 day ago

7 weeks 2 days ago

8 weeks 1 day ago

12 weeks 1 day ago

16 weeks 4 hours ago

20 weeks 10 hours ago

20 weeks 5 days ago

30 weeks 5 days ago

34 weeks 6 days ago