The Emerald Triangle mourns the passing of BE Smith, the legendary Trinity County grower who did time in federal prison for openly cultivating cannabis under California's medical marijuana law—throwing down the proverbial gauntlet to Washington DC from his mountain homestead. His bold action put the Justice Department on the spot, and helped prompt a change in federal policy.

The Emerald Triangle mourns the passing of BE Smith, the legendary Trinity County grower who did time in federal prison for openly cultivating cannabis under California's medical marijuana law—throwing down the proverbial gauntlet to Washington DC from his mountain homestead. His bold action put the Justice Department on the spot, and helped prompt a change in federal policy.

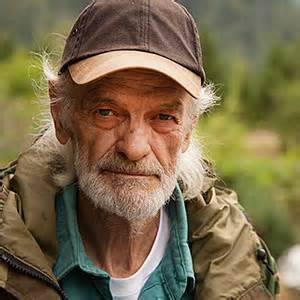

Northern California's legendary cannabis grower and audaciously outspoken activist Bailous Eugene Smith—universally known as BE—passed on at a hospital in Redding on Jan. 6, following complications from bypass surgery. He was 72 years old.

BE Smith was born in Alabama, but came to California's north country with his family while still a young boy. He did two tours of duty in Vietnam at the height of the war in the late '60s, and came back suffering from PTSD. He initially took to alcohol, but soon "transitioned to pot," in the words of his daughter-in-law, Rose Betchart Smith.

For a while he worked as a tree-feller in the local timber industry, but in the late '70s became a real outlaw—joining a group of gold prospectors in the deep back-country of the remote and rugged Trinity Alps, living off the land in the wilderness. Although the US Forest Service considered them trespassers, they claimed legitimacy under the 1872 mining law, which allows claim-staking on the public lands. The USFS admitted in 1982 that it had "lost control" of some 100,000 acres of Shasta-Trinity National Forest.

The outlaw miners were cleared out in a series of raids by Forest Service enforcement and National Guard troops in 1983—a direct precursor to the militarized Campaign Against Marijuana Planting (CAMP), which began immediately thereafter.

When this reporter first interviewed Smith for High Times magazine in 1994, he told me he was sure that the elite anti-terrorist Delta Force was brought in for the raids, although the Pentagon would not confirm this. "Denny Canyon was a test run for the war on drugs," he told me, referring the gulch where the miners staked their claim.

By the early '90s, Smith had settled in Denny, the unincorporated village on the edge of the canyon, where he switched from gold prospecting to growing cannabis—initially to treat his PTSD. But he also won a clientele, as his renown as a skilled cultivator grew. Smith boasted to me that one of his clients was Merle Haggard, the country music legend who lived in neighboring Shasta County.

This period also saw Smith's emergence as a grassroots political voice. He developed a following among local growers, bikers and rednecks as a "constitutionalist" libertarian, asserting a right to grow cannabis—and drive without license or seat-belt—under his populist interpretations of English common law. "The marijuana laws don't apply to private citizens," he told me. "If you don't grow under contract to the federal government, the Marihuana Tax Act doesn't apply to you."

His advocacy made BE a link between the redneck culture of his Trinity County and the hippiedom of Humboldt to the west, bridging a divide that has been the source of much tension in the Emerald Triangle.

Smith only got bolder with the passage Proposition 215 in 1996, making California the first state in the country to allow cultivation, sale and use of medical marijuana. The following year, he started growing openly—as designated caregiver for some 30 patients around the state. One was Sister Somayah Kambui, a veteran Black Panther in Los Angeles who used cannabis to treat pain from sickle-cell anemia.

He grew 87 plants at the site, on the land of his neighbor and friend Martin Lederer, an elderly German immigrant. This number was chosen partially in sentimental reference to 1787, the year the US Constitution was signed—but also to keep the number below 99, that at which the five-year federal mandatory minimum sentence kicks in. He said patients could expect to purchase 17 ounces of untrimmed bud for $500. Paperwork indicating that he was a designated caregiver under California law was prominently posted at the grow site, and he painted the roof of a nearby shed for helicopters to see with the words: "MEDICAL MARIJUANA, CALL TRINITY COUNTY SHERIFF."

During the period he was taking this openly defiant stance, Smith won much media attention, including a segment on the Discovery Channel's "Weed Country" series.

But on Sept, 24, 1997, the grow was raided by US marshals and Forest Service agents who were choppered into Denny, and the plants were seized. In November, a federal grand jury brought felony cultivation charges against Smith. Lederer also faced charges, and a forfeiture proceeding against his property.

When I spoke to BE after the raid, he was typically intransigent. "You don't have a crime if there's no corpus delicti—the injured party," he said. "Where's the corpus delicti? There is none. The war on drugs is a scam."

Smith was defended in the Sacramento courtroom by activist attorney Tom Ballanco, who is today a Trinity resident himself. Reached for comment at his off-the-grid homestead, Ballanco recalled the arguments his team made to the jury. "We claimed a medical necessity defense, first and foremost," he says. "But we also argued that there was no federal jurisdiction, on states' rights grounds. As an intra-state matter, it didn't concern the federal government. The primacy of state law was one of BE's pet theories."

Ballanco emphasizes that the states' rights argument would actually be vindicated years later in the 2011 Cole Memo, the Justice Department document instating a policy of non-interference in state-legal cannabis cultivation or sale (recently rescinded by the Trump administration).

BE's patients were brought in to testify, inlcuding Sister Somayah, and a man who had lost his leg in a motorcycle accident and was dealing with "phantom pain." But District Judge Garland E. Burrell barred any mention of medical marijuana in their testimony, on the grounds that it was not recognized by federal law. The patients could only serve as character witnesses. Also brought in as a character witness was actor Woody Harrelson.

BE was convicted on May 21, 1999 and sentenced to 27 months. Rose Smith notes sadly that the sentence came down on Aug. 6—which was the 33rd birthday of BE Smith Jr, her husband and the defendant's son.

Smith served his time at the federal prison in Sheridan, Ore. Lederer pleaded guilty and got nine months, which he was able to serve locally. He was also able to keep his property.

After his release, Smith had to lay low for a few years, as he remained on probation. But he eventually returned to the political arena, in his trademark irreverent style. He repeatedly ran for sheriff of Trinity County—mostly as a protest candidate—and even threw his hat in the ring for governor of California in the 2003 gubernatorial recall election.

Rose Betchart Smith has this to say about the man she considered a mentor: "I am proud to be his daughter-in-law, and proud of his accomplishments as a Freedom Fighter. He taught me how to research law, speak up for the people, be a government watchdog and more."

Rose says that in his final days, BE had reflected on the current political polarization in the country, and his wish for a renewed sense of unity. "One thing he told me last month while in the hospital was that he just wanted 'Americans to be Americans'," she says.

Image from Weed Country

Recent comments

4 weeks 1 day ago

4 weeks 2 days ago

7 weeks 2 days ago

8 weeks 2 days ago

12 weeks 2 days ago

16 weeks 21 hours ago

20 weeks 1 day ago

20 weeks 6 days ago

30 weeks 6 days ago

34 weeks 6 days ago