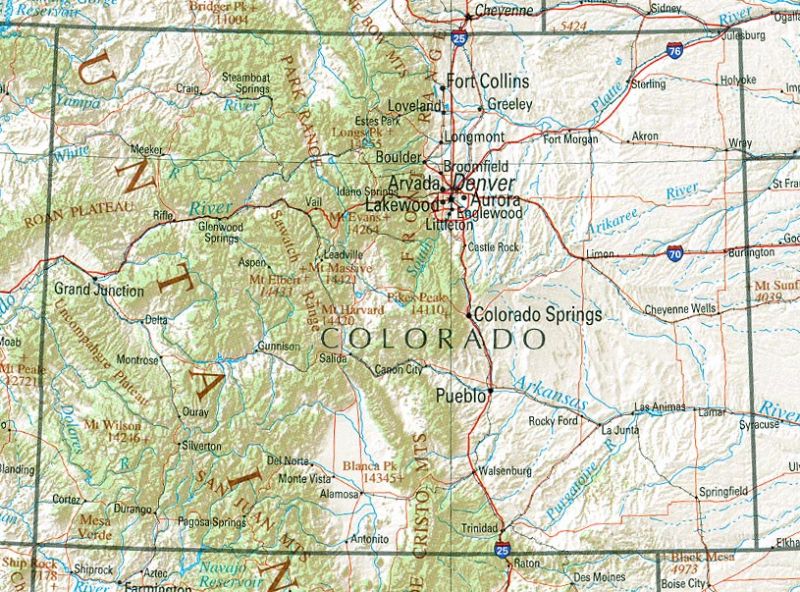

On Colorado's northeast plains, advocates of secession from the state have managed to put the question before voters in 11 counties this November —potentially bringing a split-the-state initiative to statewide vote by November 2014. As Weld County Commissioner and leading secession proponent Sean Conway explained to reporters, an "advisory" vote at the county level would require local lawmakers to request that state legislators introduce a constitutional amendment allowing the northeastern counties to go their own way. That would require two-thirds approval by both houses. Failing that, proponents could put the measure to statewide vote by collecting 80,000 signatures. Finally, the initiative would have to be approved by the US Congress. So it is an arduous process—but proponents are clearly dead serious.

On Colorado's northeast plains, advocates of secession from the state have managed to put the question before voters in 11 counties this November —potentially bringing a split-the-state initiative to statewide vote by November 2014. As Weld County Commissioner and leading secession proponent Sean Conway explained to reporters, an "advisory" vote at the county level would require local lawmakers to request that state legislators introduce a constitutional amendment allowing the northeastern counties to go their own way. That would require two-thirds approval by both houses. Failing that, proponents could put the measure to statewide vote by collecting 80,000 signatures. Finally, the initiative would have to be approved by the US Congress. So it is an arduous process—but proponents are clearly dead serious.

The proponents of secession cite Colorado's new gun-control legislation, measures protecting the rights of undocumented ("illegal") immigrants, a new law requiring electrical cooperatives to double the amount of renewable energy they use by 2020—and last year's historic cannabis legalization measure. The secession movement drives home the cultural and political divide between hippie and liberal parts of the state like Denver, Boulder and Aspen, and the conservative eastern plains. Names for the breakaway entity have been that have been facetiously floated include Uncolorado, Near Nebraska, Southern Wyoming and Coloraduh. New monikers for the crunchy areas of Rump Colorado include Potopia, Crackpotopia and Crankerado.

A similar initiative is underway in California, where Siskiyou and Modoc counites in the far north have already voted to secede, reviving a plan called the "Jefferson Declaration" that nearly succeeded in carving the new state of Jefferson out of the remote California-Oregon borderlands in 1941. Both Siskiyou and Modoc are on the northern fringe of California's cannabis-growing heartland, the Emerald Triange—where the hippie-redneck division has been a source of cultural clash for two generations now. Modoc and Siskiyou are also among those counties where local law enforcement have proclaimed a "Constitutional Sheriffs" movement—mostly in response to federal land-use policies in the National Forests, perceived as too restrictive on local logging and mining.

Plenty of cannabis is also being grown in those forests, of course. Trinity County is on board with the "Constitutional Sheriffs," and as much as they may oppose federal environmental regulations, authorities there are still cooperating in cannabis enforcement. On Aug. 29, the Trinity County Multi-Agency Narcotics Task Force—including agents of the North State Marijuana Investigation Team (NSMIT), Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Trinity County Narcotics Task Force—carried out search warrants on 23 parcels in the town of Hayfork: the latest raids in ongoing anti-cannabis efforts.

Four states have been carved from the territory of others in the history of the United States: Kentucky (from Virginia in 1792), Maine (from Massachusetts in 1820), Vermont (contested by New York and New Hampshire until 1777) and West Virginia (from Virginia in 1863). At issue in the cases of Kentucky, Maine and Vermont was the desire of pioneers and backwoodsmen to be free of distant elites—a principle that also animated the Jefferson initiative in 1941. In the case of West Virginia, of course, the issue was slavery. This time around, cannabis is emerging as a political dividing line. But in a strange irony, the conservative secessionists may be seeking closer cooperation with federal power where the weed is concerned, even as they rebel against federal oversight where control of timber, minerals and grazing lands is concerned. (LAT, Sept. 23; SF Chronicle, Sept. 8; AP, Sept. 4; Lost Coast Outpost, Aug. 30; Westword, Aug. 8; Daily Caller, June 25)

Cross-post to High Times

Image from the Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection

Comments

Six-state plan for California

io9 website reports that venture capitalist Tim Draper filed a ballot initiative in December to get a measure before California voters in 2014 to divide up the state into six new ones, named as Jefferson, North California, Silicon Valley, Central California, West California, and South California. Looking at the map of the "Six Californias" plan, we question the logic of both the boundaries and the names. E.g. "Silicon Valley" actually seems to include San Francisco, implying that the city has been reduced to a mere suburb of San Jose. It also makes no geographic sense, since San Francisco is well outside the Santa Clara Valley, obviously. "Jefferson" includes Humboldt and Mendocino counties, which were never part of the original Jefferson plan, and where hippies will likely be reluctant to join a redneck-dominated entity. "North California" is actually to the south of Jefferson, implying that Jefferson is not even an historical part of California! A more natural name for "North California" would be "Greater Sacramento," but it is telling that the present state capital doesn't get the respect won by Silicon Valley...