Cannabis advocates across the United States and the world bid a grateful farewell to Lester Grinspoon, the Harvard psychiatrist and prolific author who probably did more than any other individual to change the national conversation about marijuana, stressing the need for a more tolerant and enlightened policy.

Cannabis advocates across the United States and the world bid a grateful farewell to Lester Grinspoon, the Harvard psychiatrist and prolific author who probably did more than any other individual to change the national conversation about marijuana, stressing the need for a more tolerant and enlightened policy.

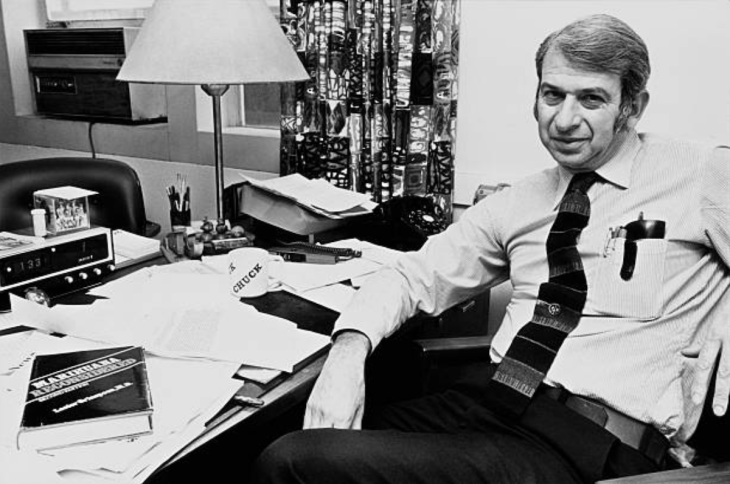

Dr. Lester Grinspoon, the renowned Harvard scholar whose works boldly challenged the cannabis stigma in an era when it was deeply entrenched in American culture, died June 25 at his home in the Boston area. His passing came unexpectedly, one day after he had celebrated his 92nd birthday.

His most pioneering work was Marihuana Reconsidered, published in 1971, and the fruit of years of research with Harvard Medical School. In addition to a review of the scientific literature and historical material, it actually included first-hand interviews with cannabis users, portrayed without prejudice—a ground-breaking notion for its time. With chapters dispassionately dedicated to deconstructing the propaganda of fear ("Psychoses, Adverse Reactions," "Crime and Sexual Excess"), it concluded with an open call for legalization.

This was given greater legitimacy by the fact that Grinspoon came to the question not as an already-convinced advocate but an objective scholar. As he would admit in a new introduction for the 1994 reprint edition: "I first became interested in cannabis when its use increased explosively in the 1960s. At that time I had no doubt it was a very harmful drug that was unfortunately being used by more and more foolish young people... But as I reviewed the scientific, medical, and lay literature, my views began to change. I came to understand that I, like so many other people in this country, had been misinformed and misled."

In the final paragraph of the book, he famously wrote:

Over the following decades, as the marijuana legalization movement burgeoned, Grinspoon emerged as its top intellectual authority and most respected representative.We must consider the enormous harm, both obvious and subtle, short range and long‐term, inflicted on the people, particularly the young, who constitute or will soon constitute the formative and critical members of our society by the present punitive, repressive approach to the use of marijuana. And we must consider the damage inflicted on legal and other institutions when young people react to what they see as a confirmation of their view that those institutions are hypocritical and inequitable. Indeed the greatest potential for social harm lies in the scarring of so many young people and the reactive, institutional damages that are direct products of present marijuana laws. If we are to avoid having this harm reach the proportion of a national disaster with in the next decade, we must move to make the social use of marijuana legal.

He was among the very first to speak out for legalization on Capitol Hill. In 1977, he provided lengthy written testimony to the House Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse & Control, concluding optimistically: "Whatever the cultural conditions that have made it possible, there is no doubt that the discussion about marihuana has become increasingly sensible. We are gradually becoming conscious of the irrationality of classifying this drug as one with a high abuse potential and no medical value. If the trend continues, it is likely that within a decade marihuana will be sold in the United States as a legal intoxicant."

Of course the backlash in Reagan revolution upset the timeline of Grinspoon's prediction. But he did live to see a legal market became a reality in several states—and could claim a good share of the credit for helping to bring this about.

Bringing science to advocacy work

Massachusetts native Grinspoon would be compelled by the conclusions to emerge from his own research to take an advocacy position, eventually joining the board of directors of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML).

Years after the release of Marihuana Reconsidered, Grinspoon would reveal that one of the cannabis users quoted at length in the book—identified only as "Mr. X"—was in fact Carl Sagan, the Cornell astrophysicist who a decade later would become a celebrity popularizer of science. Sagan's closing remarks as Mr. X in the book have often been quoted: "The illegality of cannabis is outrageous, an impediment to full utilization of a drug which helps produce the serenity and insight, sensitivity and fellowship so desperately needed in this increasingly mad and dangerous world."

Grinspoon credited Sagan as the key personality that opened his mind on the cannabis question.

Grinspoon also testified on behalf of John Lennon at his 1973 deportation hearing—a proceeding initiated by the US government on the basis of his prior hashish arrest in England. As Grinspoon related to an amused audience at the 2011 NORML conference in Denver, the Nixon administration really "wanted to get Lennon out of the country because he was effectively protesting the Vietnam War." The immigration officers overseeing the hearing weren't even clear on whether hashish was a form of marijuana, Grinspoon wryly recalled. The ex-Beatle was ultimately allowed to stay.

The cannabis question became poignantly personal for Grinspoon and his wife Betsy when their son Danny succumbed to cancer when he was still a young teenager. Cannabis helped him to endure the ill effects from high doses of chemotherapy. This experience propelled Dr. Grinspoon's interest in the medicinal potential of the cannabis plant. In 1993, he joined with James B. Bakalar to author Marihuana: The Forbidden Medicine. Three years later, California would become the first state to legalize medical use of cannabis.

Grinspoon and Bakalar first collaborated on the 1979 book Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered. They also co-authored the 1984 title Drug Control in a Free Society, a libertarian-minded critique of the entire prohibitionist paradigm.

Among Grinspoon's other books was The Long Darkness: Psychological and Moral Perspectives on Nuclear Winter. Released in 1986, at the height of the Reagan-era arms race, it examined the ethics of the then-current policies in light of the potential impacts of nuclear war on the planet's climate.

Despite his achievements, Grinspoon was twice turned down for a full professor position at Harvard—something he attributed to the lingering cannabis stigma. According to a 2018 profile on Grinspoon in the Boston Globe, he believed "an undercurrent of unscientific prejudice against cannabis among [Harvard] faculty and school leaders doomed his chances."

But whatever status he sacrificed for his beliefs among the academic establishment was made up for in the esteem he won from the advocacy community. In 1990 he received the Alfred R. Lindesmith Award for Achievement in the Field of Scholarship & Writing from the Drug Policy Foundation. In 1999, NORML established the Lester Grinspoon Award for Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Marijuana Law Reform, the organization's highest honor—with Grinspoon, of course, the first recipient. Dr. Grinspoon served as a member of the NORML advisory board until his death.

As NORML wrote in a farewell statement upon the passing of the courageous scholar: "Dr. Lester Grinspoon led the way to insist that our marijuana policies be based on legitimate science. He made it possible for us to have an informed public policy debate leading to the growing list of states legalizing the responsible use of marijuana."

Cross-post to Cannabis Now

Image: NORML

Recent comments

5 weeks 5 days ago

5 weeks 6 days ago

8 weeks 6 days ago

9 weeks 6 days ago

13 weeks 6 days ago

17 weeks 4 days ago

21 weeks 5 days ago

22 weeks 3 days ago

32 weeks 3 days ago

36 weeks 3 days ago